Every Man, Woman and Child in Guyana Must Become Oil-Minded – Column 156

As feared, the Government ignored calls to refer the Oil Pollution Prevention, Preparedness, Response, and Responsibility Bill to a Select Committee and advanced it to a second reading and passage. Listening to the exchange in the National Assembly yesterday, it was entertaining to see how members accused each other across the House of not having read the Bill. Standing among these was the Minister of Natural Resources, who spent most of his time discussing the IMF, the OAS, EITI, the World Bank, and the NRF.

Yesterday’s column spoke of the maze of institutions created by this Bill. At the top of the pile is the Civil Defence Commission (CDC), currently a loose body that, in a single clause, is transformed into a body corporate, a legal entity headed by a Governing Board. There is nothing to suggest how this body will relate to the Environmental Protection Agency and to the Ministry of Natural Resources.

One thing is sure: any idea of a Petroleum Commission is now dead, as dead as Review and Renegotiate. Another certainty is that the CDC has no capacity in personnel and assets to carry out the functions and duties imposed on it by this Bill. As the Competent National Authority, the CDC is required to develop, prepare, and publish a National Oil Spill Contingency Plan to guide all coordination and response operations of oil spill incidents or potential oil spill incidents. It faces an immediate uncertainty: the Bill provides no guidance on development processes, consultation requirements, approval mechanisms, or update frequency. Even though it is a “National” plan, there is no indication whether the plans of various companies and sectors, including those of the oil companies, are to be incorporated into the National Plan.

The other organisational issue is how this Bill will alter the CDC’s prior focus – the management of disasters.

The prosecution puzzle

Another feature of the Bill is the bewildering array of offences – from failing to submit plans to refusing to respond to spills – with penalties ranging from fines to mandatory three-year prison terms. Yet remarkably, it fails to specify who will bring these criminal charges or which courts will hear them. The legislation simply states that responsible parties “commit an offence” and “shall be liable on summary conviction” or “on conviction on indictment,” leaving prosecutors, defendants, and courts to guess whether the Director of Public Prosecutions, the CDC, the EPA or some other authority has the power to initiate proceedings. The Attorney General did not name the Office of the DPP as one of the persons and organisations consulted.

This omission creates potential chaos where administrative agencies like the EPA pursue civil penalties while criminal prosecutors pursue parallel charges in different courts for the same conduct.

The link with the Deal of the Millennium

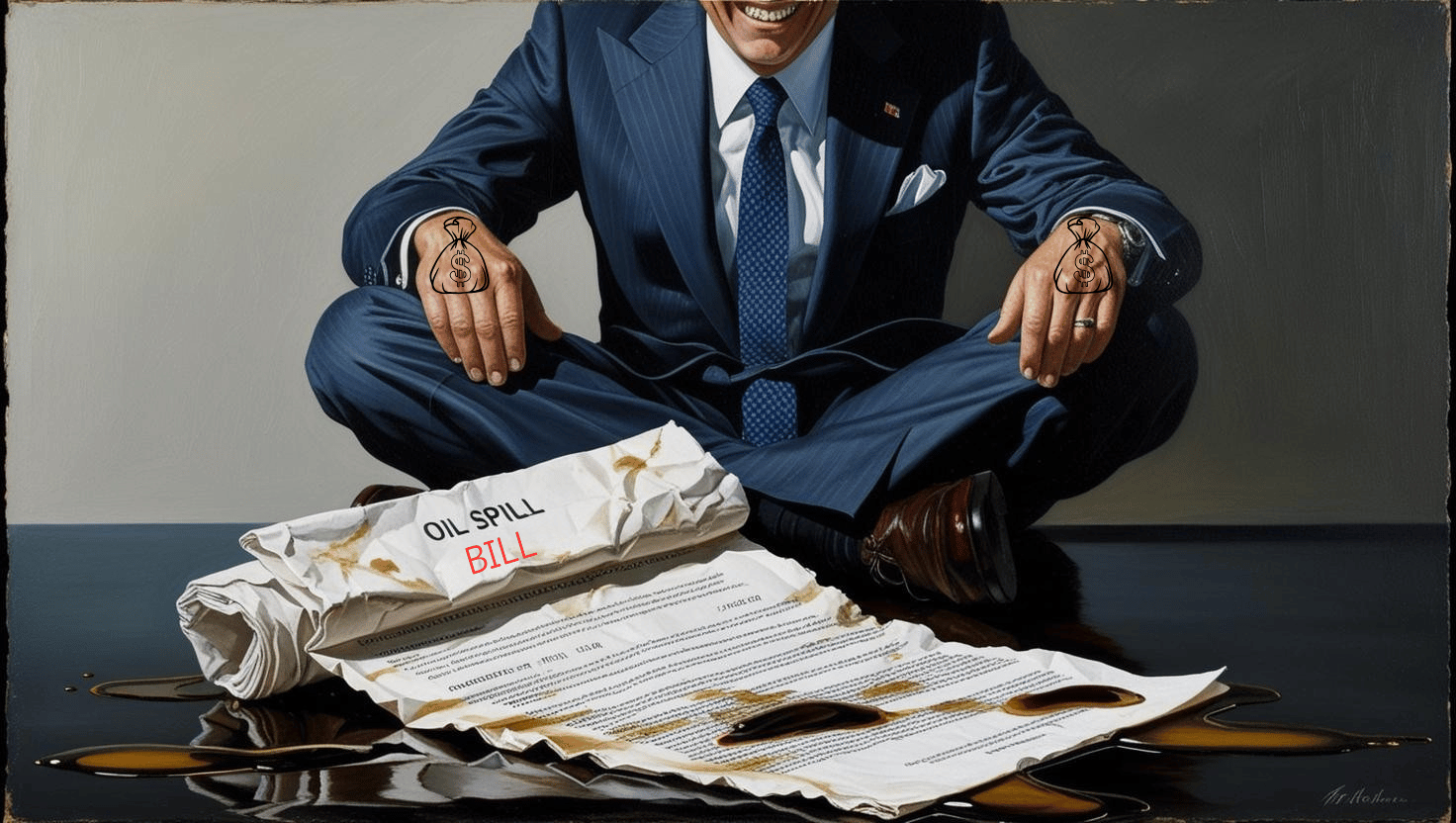

The greatest threat from any environmental disaster comes from the operators of the Stabroek Block, which controls over eleven billion barrels of oil. Clause 10 of the Bill requires oil companies (the “responsible party”) to submit their contingency plans which must align with or be incorporated into the National Oil Spill Contingency Plan. The problem is that the 2016 Agreement has its own provisions dealing with environmental disasters, including oil spills. Yet, this Bill conspicuously avoids directly addressing how it interacts with the existing 2016 Petroleum Agreement between Guyana and the ExxonMobil consortium, particularly the Agreement’s powerful stability clause in Article 32.

Oil companies will therefore have two obligations and two options. They can point to either the Agreement or the Bill, whichever is more favourable, while taxpayers fund the oversight system.

International outlier

Almost every speaker on the Government side spoke of the standing of Guyana’s Bill, with several countries cited as sources from which this Bill was drawn. That is not supported by evidence from several countries. The United States’ Oil Pollution Act of 1990 makes operators the primary responders and creates a trust fund financed by a tax on oil companies. Norway imposes criminal liability on executives for willful violations and maintains strict liability without regard to fault. Canada requires operators to submit prevention plans while maintaining clear operator responsibilities. The UK’s approach focuses on vessel discharges with consolidated controls.

What makes Guyana’s Bill particularly troubling is its funding model – every other country either requires operators to pay directly or ensures operator liability, whereas Guyana’s taxpayers fund the entire bureaucracy. I found no other country with as many layers of bodies and overlapping jurisdictions. The effect of this Bill is that many of the costs are shifted from operators to taxpayers.

Conclusion

The Government has used its majority in the twilight of the 12th Parliament to rush this Bill through its second and third readings to passage. However, there is no funding for the massive structure and functions contemplated in the Bill, which, along with a range of marine, air, and land transportation assets and technical facilities, will be required to give the Bill a chance of success. Passage of the Bill will prove to be the easy part.

Christopher Ram