The 2016 Stabroek Block oil contract between the oil companies and the Government of Guyana violates many of Guyana’s laws compared to the original 1999 contract, according to local legal experts. The Government seems content to ignore our own national laws. None of the violations in this oil contract have been challenged in court as yet.

Guyana’s leadership seem satisfied to let the oil companies accelerate extracting the nation’s oil while flaring the gas, without heeding national laws. The environmental permit to Esso clearly prohibits routine flaring and requires Esso to reinject the associated gas at its cost. Yet, the government has not yet taken legal action available in current EPA rules to stop the flaring.

Major producers such as Saudi Arabia have continued to limit their oil production to influence price. Guyana’s production operations ignore its own laws, at its own peril, to let the oil companies pump beyond the pumping capacity specification of 120,000 barrels a day that was agreed to as a safe quantity.

In the 1999 Stabroek contract, a key law was broken with the award of the 600 blocks when the maximum award for any single license should be 60 blocks. This is stated in the 1986 Petroleum Act, regulation 13(2). That Act makes reference to a graticular block, a unit of area of the seabed. The Act states the maximum allowed for a single license is 60 blocks but for the Stabroek block, the then Government gave away 10 times that amount for a single license.

One would have thought Guyana would have accumulated much more wisdom 17 years later, from the 1999 contract to the new 2016 contract. However, the 2016 Stabroek oil contract inherits the graticular block violation and adds a few more outrageous violations.

Another violation of Guyana’s laws is the Stabroek contract allows the oil companies to pay no taxes. Why is it reasonable for one of the richest and largest companies in the world to have millions of US dollars in taxes paid for the contractor and their subsidiaries by one of the poorest and smallest countries in the Western Hemisphere? The Guyanese airports, wharves and roads that the oil companies use to conduct their operations are paid for by the Guyanese tax payers without a cent from taxes on oil production going towards Guyana’s budget? How is that fair to the citizens of Guyana?

The “stability clause” in the contract prevents any government – current or future – from ever adjusting the unfair terms of the contract without compensating the oil companies. This clause is contrary to Article 65(1) of the Constitution of Guyana. If the government represents the people of Guyana, surely it would uphold the constitution. It appears the people’s well-being and interests are being harmed in the present and future.

There are examples where citizens have used the laws of Guyana successfully against the oil companies for the benefit of all Guyanese. Recently, Dr. Troy Thomas, former president of Transparency Institute Guyana, won a case that reduced the Environmental Protection license from the improperly issued 24 years to 5 years as per Guyana’s law. OGGN has discussed some serious violations above where enforcement of our laws would result in Guyana recouping estimated billions in US dollars from a flawed Stabroek Oil contract. Why isn’t the government enforcing these laws on behalf of the Guyanese people?

The longer these violations persist under Guyana’s laws, the cumulative losses plus environmental effects will harm Guyana’s oil industry itself. As with gold (Omai) and manganese, Guyana will have to face a stripped-down economy as companies close out their operations.

Apart from those legal violations, there are additional major concerns such as failure to release oil production data; failure to verify transactions in addition to audit records (audit is the process of examining and adjusting while verification is to prove the truth of a transaction); failure to have insurance through the oil companies and not secondary “shell” companies; Guyana’s inability to make unannounced production monitoring visits; Exxon not meeting local content expectations; and whether the Government not auctioning the oil blocks is a violation of Guyana’s procurement laws.

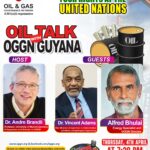

What is to be done? We suggest that Citizens’ Groups from Civil Society should embark in a strong advocacy with the Guyana Government to press for renegotiation of the Production Sharing Agreement, stricter EPA permits, and creation of an enabling operational process for stricter audits of oil companies expense accounts and related issues in oil production. If persuasion strategies fail, perhaps Citizen Initiative is needed to file appropriate action to nullify the seemingly illegal aspects of the Production Sharing Agreement of the Stabroek Block. OGGN Network