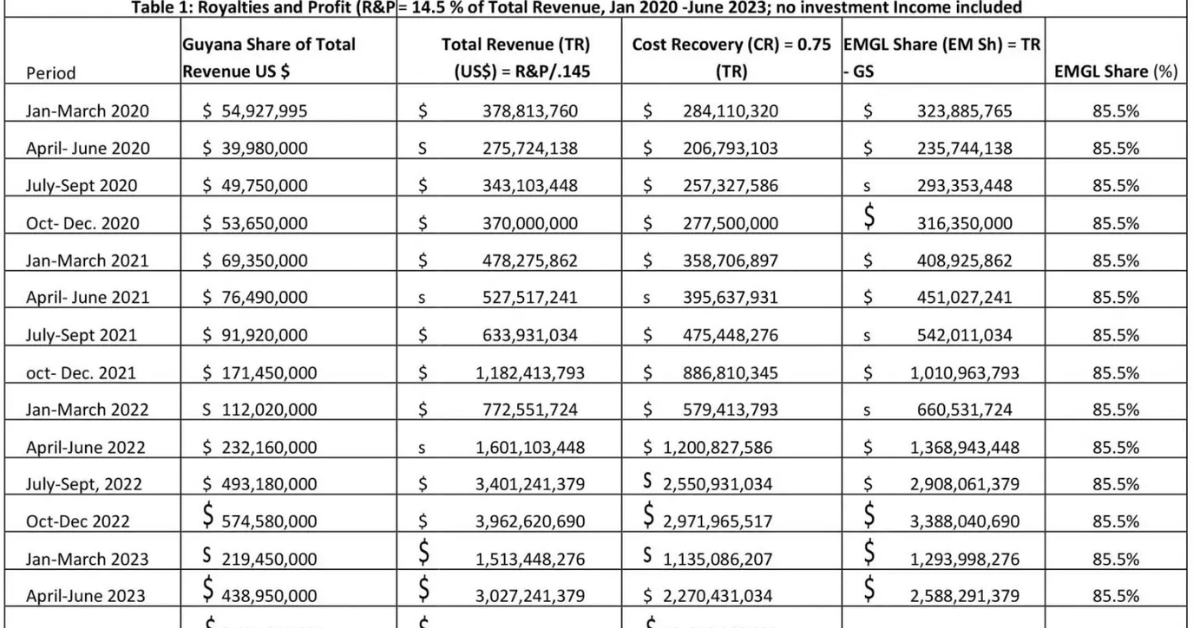

According to a Bank of Guyana Report, the share of Total Revenue that Guyana received for profit oil and royalty between January 2020 and June 2023 is US$2.68 billion. And from this amount, it can be derived that total Revenue (TR) is US$18.47 billion, the total cost recovery is US$13.85 billion, and the share of total revenue captured by ExxonMobil Guyana Limited (EMGL) is US$15.79 billion (Table 1).

Since EMGL’s share of total revenue is US$15.79 billion and the capital cost of Liza 1 and 2 is US$9.5 billion, it is therefore very clear that the total capital cost of Liza 1 and 2 have already been fully recouped, leaving a balance US$6.29 billion. With such a large balance (US$6.29 billion), it is posited that after subtracting the operating cost (currently unknown) from US$6.29 billion, EMGL will still have a very healthy positive balance. This will allow EMGL, Hess and CNOOC to go laughing all the way to the bank; keep their shareholders happy with high returns; accelerate oil extraction from new wells, given that no ring fencing exists; and build an exit strategy that by-passes all regulation, so as to ensure that only zero dollars in assets are identified at the end of the project.

In the meantime, instead of investing in human development projects, poor Guyana will be spending some of its 14.5 percent (US$2.67 billion) on the following items: paying auditors’ fees; absurdly paying EMGL taxes to the Guyana Revenue Authority, and issuing fake receipts to EMGL; paying EMGL and Guyana lawyers’ fees for Arbitration sessions outside of Guyana; and hoping that there is no environmental disaster, a liability which Guyana will have to pay without a significant contribution from EMGL. So, is this a fair deal? Would future generations not ridicule us for being poor managers of our oil resources? Policymakers, please reclaim our patrimony, for no company should have a chokehold on a sovereign nation. Wake-up Guyana before the Oil Wells in the Stabroek run dry!

Meanwhile, it should be noted that even without knowing how many barrels of oil have been extracted, the average cost of a barrel of oil is known. For instance, the Total Cost (TC) incurred is equal to 0.75 PQ, where P is the price of a barrel of oil, and Q is the number of barrels of oil. Therefore, the average cost of a barrel of oil (ACBO) is equal to: ACBO = TC/Q = 0.75PQ/Q = 0.75P. What is offensive about this ACBO is that this average cost function includes the selling price (P) of a barrel of oil in its structure.

Consequently, this is a serious violation of any cost function, for genuine cost functions would only include the unit cost of the various inputs used, the unit cost of labor, and the number of barrels of extracted oil. Therefore, this distortion of including the price of a barrel of oil in the cost function is a flashing-red signal, indicating that the objective is not to maximize profit, but to maximize cost. In other words, profit derived under this cost recovery methodology is a misleading measure that deflates and under-reports the correct profit level for the entire life of the project.

In particular, the cost recovery method automatically increases (decreases) the cost of a barrel of oil whenever the price of a barrel of oil increases (decreases). For example, the average price of a barrel of oil during the period January 2020 to June 2023 is US$71.58 per barrel (Table 2), with an average high price of $111.36 per barrel (April-June 2022), and an average low price of US$33.75 per barrel (April- June 2020). A review of the data in Table 2 during this period will confirm this outcome.

Using the cost recovery formula with an average cost per barrel of 0.75 P, the average cost of a barrel of oil during the period is US$53.69 with a high of US$83.52 per barrel and a low of US$25.31. Not surprisingly, the highest average price (US$111.36) is correlated with the highest average cost (US$83.52), and the highest profit margin ($27.84) per barrel. Consequently, Guyana is therefore a high-cost operation that is more expensive than Brazil and the UK, where the cost per barrel ranges between US$27.62 to US$44.33. And in some other countries, the cost per barrel is less than US$10.00 per barrel.

It should also be noted that since the price of a barrel oil can change every day (oil prices are volatile), the average cost of a barrel of oil does not changes daily, because a significant share of the cost is fixed and under contract. For example, the cost of the Floating, Production, Storage and Offloading (FPSO) ship, which is the most expensive capital investment in the oil business, does not change, as it is fixed and under a contract. Similarly, wages paid to workers do not change on a daily basis, and this will most likely be the outcome of other inputs and equipment used in the business. However, this restriction on cost do not hold because of the price of a barrel of oil is imbedded in the Guyana cost function.

Finally, how did EMGL arrive at the name Whiptail for one of their projects? In Guyanese culture, that name spells bad outcomes for anyone who fails to carry out a set of conditional instructions. Similar to what the slave masters weaved, the EMGL is in our backyard with a proverbial whiptail. Figure out the rest Guyana, for it’s more than oil in a barrel.

Sincerely,

Dr. C. Kenrick Hunte

Professor and Former Ambassador

Article Originally Published At: https://www.kaieteurnewsonline.com/2023/10/10/oil-shares-to-guyana-and-emgl/